ABSTRACT

Purpose: To summarize the available evidence and answer the following question: What is the current knowledge on the performance of blood concentrates in handling sequelae after lower third molar extractions with the evidence available in systematic reviews?

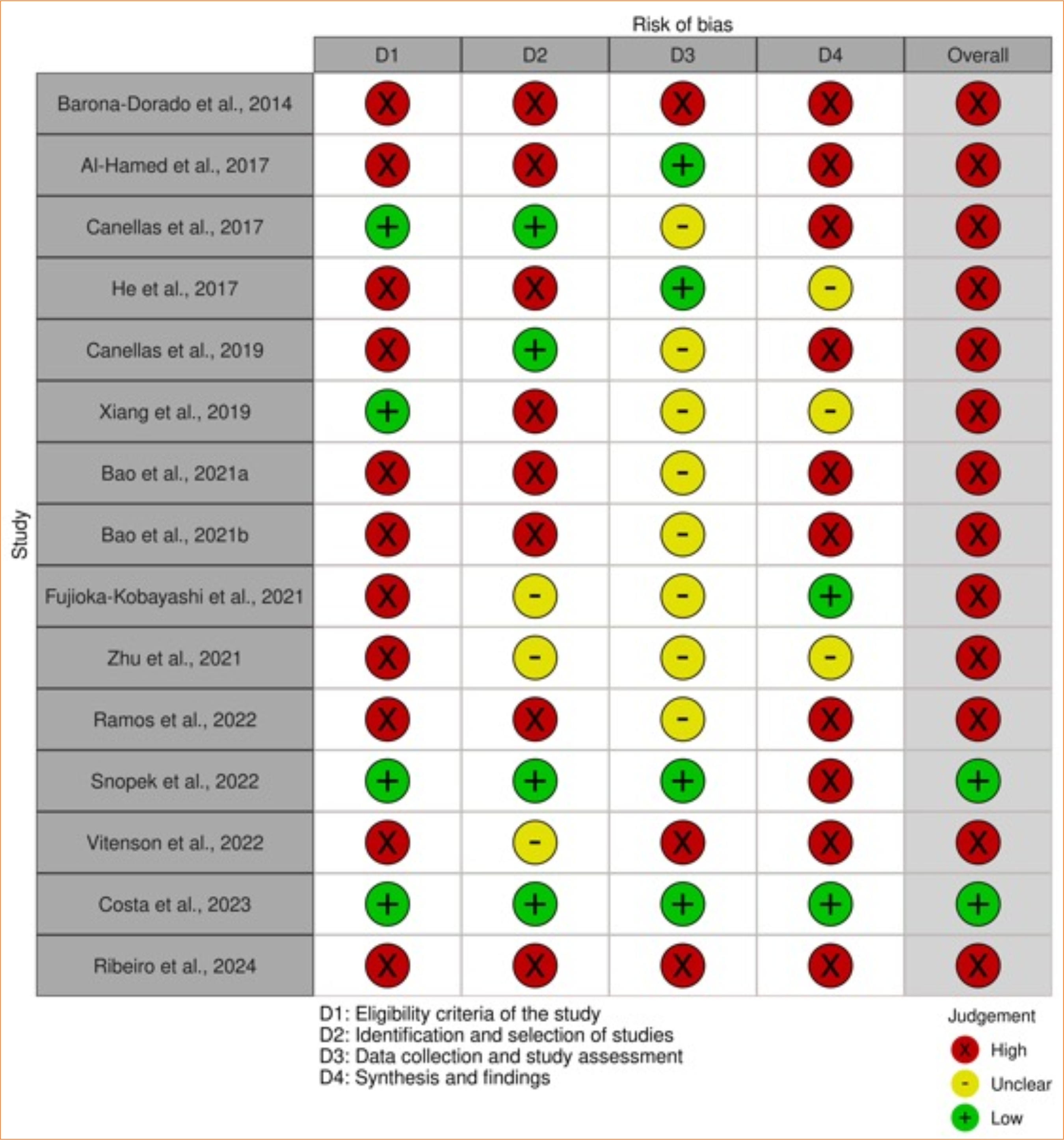

Methods: An electronic search was conducted across nine databases. The study included systematic reviews with or without meta-analyses investigating the performance of blood concentrates in managing sequelae after lower third molar extractions. The four outcomes analyzed were pain, edema, mouth opening, and alveolar osteitis. The AMSTAR-2 tool assessed the methodological quality of the included systematic reviews, while ROBIS evaluated the risk of bias.

Results: The electronic search revealed 690 records, of which 15 were eligible systematic reviews for the present study. Overall, these reviews evaluated 75 primary studies published from 2007 to 2023. According to AMSTAR-2, only one systematic review presented high methodological quality. The ROBIS tool showed two systematic reviews with a low risk, and the others had a high risk of bias.

Conclusion: The current evidence is based on only one systematic review with high methodological quality and a low risk of bias, while the others exhibited a high risk of bias and low methodological quality. Therefore, the evidence regarding the efficacy of blood concentrates in controlling sequelae following lower third molar extractions is inconclusive.

Key words

Systematic Review; Inflammation; Platelet-Rich Fibrin; Platelet-Rich Plasma

Introduction

Lower third molar extractions may be associated with sequelae, such as pain, edema, mouth-opening difficulties, and alveolar osteitis, harming patients’ postoperative quality of life1,2. Several therapeutic approaches have been indicated to control these inflammatory signs and symptoms, including drug therapy, cryotherapy, low-level laser therapy, and blood concentrates2–7.

Blood concentrates originate from autologous blood and primarily consist of platelets, fibrin, leukocytes, and growth factors8. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is the first-generation blood concentrate, presenting disadvantages such as the need for more than one step for production and anti- and procoagulant addition9,10. Studies have developed blood products, such as platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), later renamed leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF)11. New centrifugation protocols developed from L-PRF resulted in advanced platelet-rich fibrin (A-PRF), advanced platelet-rich fibrin plus (A-PRF+), and concentrated growth factor (CGF)10–12.

Blood concentrates are fibrin-based biomaterials containing cells, matrix proteins, pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators, and growth factors, showing positive performance in handling postoperative sequelae, such as pain, edema, trismus, and alveolar osteitis13,14. Hence, inflammatory response modulation occurs, optimizing primary hemostasis, chemotaxis, angiogenesis, and mitogenesis of endothelial cells14.

Systematic reviews have analyzed the effect of blood concentrates on managing postoperative sequelae, such as pain, edema, mouth opening, and alveolar osteitis, showing conflicting results and several recommendations for randomized clinical trials with larger samples and more homogeneous methodologies15–18. Moreover, the overall syntheses and assessments of these reviews have not occurred, which is relevant considering each review answers different research questions on the same subject. These reviews analyze different primary studies and blood concentrates, causing the referred outcome variability. Therefore, this overview summarized the available evidence and answered the following question: What is the current knowledge on the performance of blood concentrates in handling sequelae after lower third molar extractions with the evidence available in systematic reviews?

Methods

Protocol registration

The protocol of this review was created according to the PRISMA-P19 guidelines and registered a priori in the PROSPERO database (CRD42023405301) (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/). The overview was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations20.

Eligibility criteria

The study included systematic reviews with or without meta-analyses investigating the performance of blood concentrates in controlling sequelae after lower third molar extractions. The four outcomes analyzed were pain, edema, mouth opening, and alveolar osteitis. There were no restrictions on year or language.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

Randomized clinical trials;

-

Studies with different objectives;

-

Case reports;

-

Animal studies;

-

In-vitro studies;

-

Letters to the editor;

-

Observational studies;

-

Systematic reviews with or without meta-analyses and with outcomes not directly related to pain, edema, mouth opening, and alveolar osteitis.

Sources of information, search, and selection of studies

The electronic searches were performed in June 2022 and updated in May 2024 in the Cochrane Library, Embase, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS), MEDLINE (via PubMed), Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) databases, and Scopus and Web of Science citation databases. The EASY and the MedRxiv preprint databases partially captured the grey literature. A search strategy was formulated for each database, respecting their syntax rules and using the Health Science Descriptors (DeCS), Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and Embase Subject Headings (Emtree) descriptors with the Boolean operators AND/OR to maximize the search. Table 1 describes the search strategy for each database.

The search results were exported to EndNote WebTM software (Thomson Reuters, Toronto, ON, Canada) to identify and remove duplicates. Next, they were exported to Rayyan QCRI software (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Doha, Qatar) for title and abstract analyses according to the described eligibility criteria. Subsequently, the full texts of the preliminary eligible studies were obtained and evaluated. Microsoft Word 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, United States of America) assisted in simultaneously evaluating grey literature results. Two eligibility reviewers (VLA and CMM) performed this entire process independently. Divergences were solved after consulting with a third eligibility reviewer (LRP).

Data collection

After selecting the articles, two reviewers (VLA and CMM) extracted the following information: author, year, and journal of publications; research objective; blood concentrate type; searched databases and period; primary studies included in the systematic reviews; risk of bias assessment tools of the studies included in the systematic reviews; and primary results and conclusions. The reviewers (VLA and CMM) underwent a calibration exercise to ensure consistency during data extraction by jointly extracting information from an eligible study. In case of missing data, the corresponding authors of the eligible studies were contacted via e-mail, with three weekly contact attempts for up to a month.

Critical assessment of individual evidence sources

Three reviewers (VLA, CMM, and LRP) analyzed the methodological quality of the included systematic reviews using the AMSTAR-2 critical assessment tool21. This tool contains 16 questions (seven critical and nine non-critical), and their answer options were “yes,” “partially yes,” “no,” or “no meta-analysis performed.” The methodological quality was low if one critical question had a “no” response and critically low if two or more critical questions had “no” answers.

Risk of individual bias in the studies

Three reviewers (VLA, CMM, and LRP) independently assessed the risk of bias in the included systematic reviews using the ROBIS tool for evaluating the risk of bias in systematic reviews22.

Initially, they analyzed four domains from which biases might have been introduced in a systematic review:

-

Eligibility criteria;

-

Identification and selection of articles;

-

Data collection and study assessment;

-

Synthesis and results.

Moreover, each domain has five or six signaling questions with the following possible answers: “yes (Y),” “probably yes (PY),” “probably no (PN),” “no (N),” “not informed (NI),” or “not applicable (NA).” Later, the overall risk of bias was evaluated during the interpretation of review findings, considering whether it identified limitations within the described domains.

All reviewers agreed on the decisions about the scoring system and cutoffs before analyzing biases. The authors determined the classification system for the bias of each domain as a “low risk” if all signaling questions scored Y/PY, “unclear risk” if only one question received PN/N/NI, and “high risk” if more than one question scored PN/N/NI. Moreover, the overall risk of bias regarding each systematic review was low if all four domains had a “low risk” or only one had an “unclear risk,” moderate if two or more domains had an “unclear risk,” and high if one or more domains had a “high risk.”

Results

Selection of systematic reviews

The study identification process found 690 records. After removing duplicates and reading the titles and abstracts, only 17 records were fully assessed for eligibility criteria, of which two were eliminated. Finally, 15 systematic reviews were selected15–18,23–33. The list of references of the eligible studies were carefully searched but did not reveal additional systematic reviews. Figure 1 details the study selection in a flowchart.

Characteristics of the included systematic reviews

The analysis comprised systematic reviews published between 2007 and 2024. One study was published in Chinese28, and the others in English. There were similarities in the search databases, with all reviews including MEDLINE (via PubMed). Additionally, seven systematic reviews manually searched journals or the list of references of their primary studies16,17,23,24,29,31,32. Table 2 describes the main characteristics of the included systematic reviews.

These reviews evaluated 75 primary studies published between 2007 and 2023, with 32 common studies across multiple systematic reviews. Figure 2 illustrates the overlap of primary studies.

Considering the heterogeneity level regarding primary studies’ designs (parallel or split mouth), samples, measurement methods, and differences in the postoperative assessment of pain, edema, and trismus, two systematic reviews could not perform a meta-analysis for these outcomes15,33. Table 3 describes the main results of the systematic reviews.

Critical assessment of individual evidence sources

According to the AMSTAR-221 analysis, only one study presented high methodological quality33, while six studies15,16,18,25,31,33 demonstrated low methodological quality, and the other systematic reviews were critically low17,23,24,26–30. Table 4 summarizes the responses of each systematic review to the AMSTAR-221 questionnaire.

Risk of individual bias of the eligible studies

Only two systematic reviews31,32 showed low risk, and the others had a high risk of bias15–18,23–30,33. There were relevant concerns regarding the risk of bias, including:

-

The absence of a previous study protocol registration;

-

The absence of a comprehensive electronic search in grey literature databases and with additional strategies;

-

The absence of a definite mention of at least two eligibility reviewers in the methodological steps of the systematic review;

-

The absence of sensitivity analyses;

-

Primary studies with a high risk of bias;

-

Protocol deviations;

-

Data interpretation focused on statistically different results.

Figure 3 summarizes the overall findings of the risk of bias assessment.

Discussion

The present overview analyzed the current knowledge on the performance of blood concentrates in handling sequelae after lower third molar extractions with the evidence available in systematic reviews. Considering the surgical nature and complexity, third molar removal may be associated with postoperative sequelae, such as pain, edema, mouth-opening difficulties, and alveolar osteitis2. The healing process involves a highly coordinated sequence of biochemical, physiological, cellular, and molecular responses to restore tissue integrity. Blood concentrates have been extensively used to improve tissue repair and modulate the postoperative inflammatory process34,35.

Only two systematic reviews15,32 evaluated PRP, and the evidence available for using PRP in lower third molar extractions is scarce. Barona-Dorado et al.15 included three primary studies36–38 in the cited systematic review15, showing conflicting results regarding the efficacy of PRP in controlling pain, mouth opening, and alveolar osteitis. Two primary studies37,38 did not present methodological flaws in the clinical trials but showed result interpretation biases. One of the articles38 affirmed that PRP significantly reduced pain levels but did not provide any value (mean and standard deviation). It did not determine the method for diagnosing alveolar osteitis and analyzed the variables jointly between upper and lower third molar sockets either. The other study37 did not provide objective data for the analyzed variables and had a small sample. It is worth noting that this included systematic review15 also presents methodological performance biases. The risk of bias analyzed in the ROBIS tool22 showed that, despite determining the study objective, there was no review question. Moreover, the review neither performed a manual search in the references of the included primary studies nor mentioned the participation of two reviewers during data collection and the risk of bias classification in said studies.

Costa et al.32 selected nine studies assessing PRP performance39–47. Five of these articles39,40,43,45,46 reported statistically favorable outcomes for the group treated with the blood concentrate, four40,42,43,45 concluded that PRP significantly reduced edema compared to blood clots, and three43,45,46 presented a lower occurrence of trismus. Although the study by Costa et al.32 had a high methodological quality according to AMSTAR 221 and a low risk of bias according to ROBIS22, the results require careful interpretation, as the primary studies assessing PRP performance exhibited a moderate to high risk of bias.

Conflicting findings also appeared for the role of L-PRF in controlling postoperative sequelae after lower third molar removal. Most included systematic reviews presented favorable conclusions regarding the efficacy of blood concentrates16,17,24,26–30,32. However, it is worth noting that three of these investigations16,27,28,32 also highlighted outcome limitations and the need for randomized clinical trials with larger samples and a more homogeneous methodology for a higher comparison effect. Except for the study by Costa et al.32, the risk of bias analysis with the ROBIS tool22 revealed that all reviews present at least a few methodological flaws concerning the lack of reference to a registration protocol24,26–29, language limitations17,26,30, or the absence of a definite mention of at least two eligibility reviewers during study selection24,28, data extraction16, and risk of bias assessment24,26,28 of primary studies. Some methodological flaws, such as the lack of a previous registration protocol, may promote imprecise conclusions, as it is hard to know whether these criteria were established in advance and guided the reviewers’ steps during the review or were determined or modified in the review process21,22. Therefore, the findings of the referred systematic reviews must be carefully interpreted considering the identified methodological limitations to prevent precipitated or imprecise conclusions.

Some systematic reviews included in the present overview did not have sufficient evidence to indicate the use of PRF after lower third molar extraction23,25,31. Including patients with lower third molars at varying degrees of inclusion/impaction in a single sample may have introduced biases in clinical trial results23. Additionally, surgical difficulty presents a statistically significant relationship with the intensity of postoperative sequelae48,49. It is worth noting that one systematic review23 presented a high risk of methodological bias due to the lack of reference to previous study protocol registration, the absence of a comprehensive electronic search in grey literature databases, the absence of a definite mention of at least two eligibility reviewers during study selection and risk of bias assessment, and the absence of sensitivity analyses. Another systematic review with a high risk of bias25 needs careful interpretation because, except for one of its primary studies50, the others did not present randomized clinical trial registrations, and the statistically insignificant results might have been hidden in the final publication, introducing result interpretation biases. Also, the primary studies of one of the included systematic reviews31 were split mouth and double-blind clinical trials, and the statistical methods used in the meta-analysis allowed a reliable interpretation of results. The statistical methods of the meta-analysis allowed a reliable interpretation of results, but the methodological heterogeneity in measuring edema and insufficient information on alveolar osteitis limited evidence availability. Consequently, a meta-analysis for postoperative pain was only feasible in three randomized clinical trials from the same systematic review31, highlighting the limitations of available evidence.

Our overview showed that A-PRF reduced pain in the first30,32, second18, third18,27,32, and seventh32 postoperative days. As for trismus and edema, A-PRF promoted higher reduction during and after the third postoperative day18,32. These results seem debatable because the release of growth factors through A-PRF occurs for 10 days, and the physiological inflammatory response appears immediately after the tissue lesion51,52. Thus, these data should be carefully interpreted because randomized clinical trials presented methodological heterogeneity, potential result interpretation biases18, methodological flaws for not mentioning the predefined registration protocol28, restrictions on publication language18, or the absence of two reviewers during study selection and data extraction of the primary studies28.

While systematic reviews are essential for evidence-based decision-making, accepting their results without a critical assessment may provide improper conclusions21. A critical evaluation should involve deep knowledge of the referred therapy and the physical and biological blood concentrate properties, indications, advantages, and limitations. Therefore, the limitations of this overview stem from the high heterogeneity and risk of bias of the included systematic reviews and their primary studies, complicating the establishment of definitive evidence. However, it is worth noting that the data for clinical decision-making on blood concentrate use should be carefully interpreted, as a detailed analysis showed relevant methodological flaws in apparently robust systematic reviews on the topic.

Additionally, systematic reviews of high-quality randomized controlled trials are essential to provide accurate evidence on this topic. In this aspect, high-quality randomized controlled trial should present an adequate randomization process, sample size calculation, blinding of operator, patient and outcome assessor, an adequate follow-up period, and protocol registration.

Conclusion

Biological factors inherent to blood concentrates are promising for optimizing tissue repair. However, the current evidence from systematic reviews remains regarding the efficacy of these products in managing sequelae after lower third molar extractions.

Randomized clinical trials with methodological standardization are first required for considering systematic reviews as adequate references for evidence-based decision-making. Moreover, systematic reviews must be performed according to scientifically established guidelines to minimize biases and ensure methodological rigor.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

-

Research performed at Post-Graduation Program in Dentistry, School of Dentistry, Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Uberlândia (MG), Brazil. Part of PhD degree thesis. Tutor: Prof. Luiz Renato Paranhos.

-

Funding

Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível SuperiorFinance Code 001Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e TecnológicoThere is no specific grant number for this funding.Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas GeraisThere is no specific grant number for this funding.

Data availability statement

All data sets were generated or analyzed in the current study.

References

-

1 McGrath C, Comfort MB, Lo EC, Luo Y. Changes in life quality following third molar surgery--the immediate postoperative period. Br Dent J. 2003;194(5):265–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4809930

» https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4809930 -

2 Cho H, Lynham AJ, Hsu E. Postoperative interventions to reduce inflammatory complications after third molar surgery: review of the current evidence. Aust Dent J. 2017;62(4):412–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/adj.12526

» https://doi.org/10.1111/adj.12526 -

3 Juhl GI, Norholt SE, Tonnesen E, Hiesse-Provost O, Jensen TS. Analgesic efficacy and safety of intravenous paracetamol (acetaminophen) administered as a 2 g starting dose following third molar surgery. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(4):371–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.004

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.004 -

4 Rullo R, Addabbo F, Papaccio G, D’Aquino R, Festa VM. Piezoelectric device vs. conventional rotative instruments in impacted third molar surgery: relationships between surgical difficulty and postoperative pain with histological evaluations. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41(2):e33–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2012.07.007

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2012.07.007 -

5 Larsen MK, Kofod T, Christiansen AE, Starch-Jensen T. Different dosages of corticosteroid and routes of administration in mandibular third molar surgery: a systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2018;9(2):e1. https://doi.org/10.5037/jomr.2018.9201

» https://doi.org/10.5037/jomr.2018.9201 -

6 Tenis CA, Martins MD, Gonçalves MLL, Silva DFTD, Cunha Filho JJD, Martins MAT, Mesquita-Ferrari RA, Bussadori SK, Fernandes KPS. Efficacy of diode-emitting diode (LED) photobiomodulation in pain management, facial edema, trismus, and quality of life after extraction of retained lower third molars: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(37):e12264. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000012264

» https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000012264 -

7 Larsen MK, Kofod T, Starch-Jensen T. Therapeutic efficacy of cryotherapy on facial swelling, pain, trismus and quality of life after surgical removal of mandibular third molars: A systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46(6):563–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12789

» https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12789 -

8 Ehrenfest DMD, Bielecki T, Mishra A, Borzini P, Inchingolo F, Sammartino G, Rasmusson L, Everts PA. In search of a consensus terminology in the field of platelet concentrates for surgical use: platelet-rich plasma (PRP), platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), fibrin gel polymerization and leukocytes. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13(7):1131–7. https://doi.org/10.2174/138920112800624328

» https://doi.org/10.2174/138920112800624328 -

9 Choukroun J, Diss A, Simonpieri A, Girard MO, Schoeffler C, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, Dohan DM. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): a second-generation platelet concentrate. Part IV: clinical effects on tissue healing. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101(3):e56–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.011

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.011 -

10 Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, Gogly B. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): a second-generation platelet concentrate. Part I: technological concepts and evolution. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101(3):e37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.008

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.008 -

11 Choukroun J, Ghanaati S. Reduction of relative centrifugation force within injectable platelet-rich-fibrin (PRF) concentrates advances patients’ own inflammatory cells, platelets and growth factors: the first introduction to the low speed centrifugation concept. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018;44(1):87–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-017-0767-9

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-017-0767-9 -

12 Sato A, Kawabata H, Aizawa H, Tsujino T, Isobe K, Watanabe T, Kitamura Y, Miron RJ, Kawase T. Distribution and quantification of activated platelets in platelet-rich fibrin matrices. Platelets. 2022;33(1):110–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537104.2020.1856359

» https://doi.org/10.1080/09537104.2020.1856359 - 13 Alissa R, Esposito M, Horner K, Oliver R. The influence of platelet-rich plasma on the healing of extraction sockets: an explorative randomised clinical trial. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2010;3(2):121–34.

-

14 Daugela P, Grimuta V, Sakavicius D, Jonaitis J, Juodzbalys G. Influence of leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF) on the outcomes of impacted mandibular third molar removal surgery: A split-mouth randomized clinical trial. Quintessence Int. 2018;49(5):377–88. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.qi.a40113

» https://doi.org/10.3290/j.qi.a40113 -

15 Barona-Dorado C, González-Regueiro I, Martín-Ares M, Arias-Irimia O, Martínez-González JM. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma applied to post-extraction retained lower third molar alveoli. A systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2014;19(2):e142–8. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.19444

» https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.19444 -

16 Canellas JVDS, Ritto FG, Medeiros PJD. Evaluation of postoperative complications after mandibular third molar surgery with the use of platelet-rich fibrin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;46(9):1138–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2017.04.006

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2017.04.006 -

17 Fujioka-Kobayashi M, Miron RJ, Moraschini V, Zhang Y, Gruber R, Wang HL. Efficacy of platelet-rich fibrin on socket healing after mandibular third molar extractions. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2021;33(4):379–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajoms.2021.01.006

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajoms.2021.01.006 -

18 Vitenson J, Starch-Jensen T, Bruun NH, Larsen MK. The use of advanced platelet-rich fibrin after surgical removal of mandibular third molars: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;51(7):962–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2021.11.014

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2021.11.014 -

19 Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349:g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647

» https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647 -

20 Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, McKenzie JE. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

» https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160 -

21 Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson E, Henry DA. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008

» https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008 -

22 Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JP, Caldwell DM, Reeves BC, Shea B, Davies P, Kleijnen J, Churchill R; ROBIS group. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:225–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005 -

23 Al-Hamed FS, Tawfik MA, Abdelfadil E, Al-Saleh MAQ. Efficacy of platelet-rich fibrin after mandibular third molar extraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75(6):1124–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2017.01.022

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2017.01.022 -

24 He Y, Chen J, Huang Y, Pan Q, Nie M. Local application of platelet-rich fibrin during lower third molar extraction improves treatment outcomes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75(12):2497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2017.05.034

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2017.05.034 -

25 Canellas JVDS, Medeiros PJD, Figueredo CMDS, Fischer RG, Ritto FG. Platelet-rich fibrin in oral surgical procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;48(3):395–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2018.07.007

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2018.07.007 -

26 Xiang X, Shi P, Zhang P, Shen J, Kang J. Impact of platelet-rich fibrin on mandibular third molar surgery recovery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19(1):163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0824-3

» https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0824-3 -

27 Bao M, Du G, Zhang Y, Ma P, Cao Y, Li C. Application of platelet-rich fibrin derivatives for mandibular third molar extraction related post-operative sequelae: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;79(12):2421–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2021.07.006

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2021.07.006 -

28 Bao MZ, Liu W, Yu SR, Men Y, Han B, Li CJ. Application of platelet-rich fibrin on mandibular third molar extraction: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2021;39(5):605–11. https://doi.org/10.7518/hxkq.2021.05.017

» https://doi.org/10.7518/hxkq.2021.05.017 -

29 Zhu J, Zhang S, Yuan X, He T, Liu H, Wang J, Xu B. Effect of platelet-rich fibrin on the control of alveolar osteitis, pain, trismus, soft tissue healing, and swelling following mandibular third molar surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;50(3):398–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2020.08.014

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2020.08.014 -

30 Ramos EU, Bizelli VF, Baggio AMP, Ferriolli SC, Prado GAS, Bassi APF. Do the new protocols of platelet-rich fibrin centrifugation allow better control of postoperative complications and healing after surgery of impacted lower third molar? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;80(7):1238–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2022.03.011

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2022.03.011 -

31 Snopek Z, Hartlev J, Væth M, Nørholt SE. Application of platelet‐rich fibrin after surgical extraction of the mandibular third molar: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Oral Surg. 2022;15(3):443–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/ors.12681

» https://doi.org/10.1111/ors.12681 -

32 Costa MDMA, Paranhos LR, de Almeida VL, Oliveira LM, Vieira WA, Dechichi P. Do blood concentrates influence inflammatory signs and symptoms after mandibular third molar surgery? A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin Oral Investig. 2023;27(12):7045–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-023-05315-5

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-023-05315-5 -

33 Ribeiro ED, de Santana IHG, Viana MRM, Freire JCP, Ferreira-Júnior O, Sant’Ana E. Use of platelet- and leukocyte-rich fibrin (L-PRF) as a healing agent in the postoperative period of third molar removal surgeries: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig. 2024;28(4):241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-024-05641-2

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-024-05641-2 -

34 Simonpieri A, Del Corso M, Vervelle A, Jimbo R, Inchingolo F, Sammartino G, Ehrenfest DMD. Current knowledge and perspectives for the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) in oral and maxillofacial surgery part 2: Bone graft, implant and reconstructive surgery. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13(7):1231–56. https://doi.org/10.2174/138920112800624472

» https://doi.org/10.2174/138920112800624472 -

35 Baslarli O, Tumer C, Ugur O, Vatankulu B. Evaluation of osteoblastic activity in extraction sockets treated with platelet-rich fibrin. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2015;20(1):e111–6. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.19999

» https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.19999 -

36 Gürbüzer B, Pikdöken L, Urhan M, Süer BT, Narin Y. Scintigraphic evaluation of early osteoblastic activity in extraction sockets treated with platelet-rich plasma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66(12):2454–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2008.03.006

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2008.03.006 -

37 Rutkowski JL, Johnson DA, Radio NM, Fennell JW. Platelet rich plasma to facilitate wound healing following tooth extraction. J Oral Implantol. 2010;36(1):11–23. https://doi.org/10.1563/AAID-JOI-09-00063

» https://doi.org/10.1563/AAID-JOI-09-00063 -

38 Haraji A, Lassemi E, Motamedi MH, Alavi M, Adibnejad S. Effect of plasma rich in growth factors on alveolar osteitis. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2012;3(1):38–41. https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-5950.102150

» https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-5950.102150 -

39 Ogundipe OK, Ugboko VI, Owotade FJ. Can autologous platelet-rich plasma gel enhance healing after surgical extraction of mandibular third molars? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(9):2305–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.014

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.014 -

40 Dutta SR, Passi D, Singh P, Sharma S, Singh M, Srivastava D. A randomized comparative prospective study of platelet-rich plasma, platelet-rich fibrin, and hydroxyapatite as a graft material for mandibular third molar extraction socket healing. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2016;7(1):45–51. https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-5950.196124

» https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-5950.196124 -

41 Gandevivala A, Sangle A, Shah D, Tejnani A, Sayyed A, Khutwad G, Patel AA. Autologous platelet-rich plasma after third molar surgery. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2017;7(2):245–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/ams.ams_108_16

» https://doi.org/10.4103/ams.ams_108_16 -

42 Bhujbal R, A Malik N, Kumar N, Kv S, I Parkar M, Mb J. Comparative evaluation of platelet rich plasma in socket healing and bone regeneration after surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2018;12(3):153–8. https://doi.org/10.15171/joddd.2018.024

» https://doi.org/10.15171/joddd.2018.024 -

43 Aftab A, Joshi UKM, Patil SKG, Hussain E, Bhatnagar S. Efficacy of autologous platelet rich plasma gel in soft and hard tissue healing after surgical extraction of impacted mandibular third molar: a prospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2020;32(4):241–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajoms.2020.03.008

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajoms.2020.03.008 -

44 Bhujbal R, Veerabhadrappa SK, Yadav S, Chappi M, Patil V. Evaluation of platelet-rich fibrin and platelet-rich plasma in impacted mandibular third molar extraction socket healing and bone regeneration: a split-mouth comparative study. Eur J Gen Dent. 2020;9(2):96–102. https://doi.org/10.4103/ejgd.ejgd_133_19

» https://doi.org/10.4103/ejgd.ejgd_133_19 - 45 Kumar A, Singh G, Gaur A, Kumar S, Numan M, Jacob G, Kiran K. Role of platelet-rich plasma in the healing of impacted third molar socket: a comparative study on Central India population. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2020;21(9):986–91.

-

46 Hanif M, Sheikh MA. Efficacy of platelet rich plasma (PRP) on mouth opening and pain after surgical extraction of mandibular third molars. J Oral Med Oral Surg. 2021;27(1):9. https://doi.org/10.1051/mbcb/2020045

» https://doi.org/10.1051/mbcb/2020045 - 47 Osagie O, Saheeb BD, Egbor EP. Evaluation of the efficacy of platelet-rich plasma versus platelet-rich fibrin in alleviating postoperative inflammatory morbidities after lower third molar surgery: a double-blind randomized study. West Afr J Med. 2022;39(4):343–9.

-

48 Phillips C, White RP Jr, Shugars DA, Zhou X. Risk factors associated with prolonged recovery and delayed healing after third molar surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(12):1436–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2003.08.003

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2003.08.003 -

49 Lago-Méndez L, Diniz-Freitas M, Senra-Rivera C, Gude-Sampedro F, Rey JMG, García-García A. Relationships between surgical difficulty and postoperative pain in lower third molar extractions. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65(5):979–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2006.06.281

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2006.06.281 -

50 Gülşen U, Şentürk MF. Effect of platelet rich fibrin on edema and pain following third molar surgery: a split mouth control study. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17(1):79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-017-0371-8

» https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-017-0371-8 -

51 Caruana A, Savina D, Macedo JP, Soares SC. From platelet-rich plasma to advanced platelet-rich fibrin: biological achievements and clinical advances in modern surgery. Eur J Dent. 2019;13(2):280–6. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1696585

» https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1696585 -

52 Pavlovic V, Ciric M, Jovanovic V, Trandafilovic M, Stojanovic P. Platelet-rich fibrin: Basics of biological actions and protocol modifications. Open Med (Wars). 2021;16(1):446–54. https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2021-0259

» https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2021-0259

Edited by

-

Section editor:

Edna Montero https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1437-1219

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

14 Mar 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

27 May 2024 -

Accepted

29 Dec 2024

Performance of blood concentrates in controlling inflammatory signs and symptoms after lower third molar extractions: an overview

Performance of blood concentrates in controlling inflammatory signs and symptoms after lower third molar extractions: an overview

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.